You don't have to dig too deep into the tech press today to hear the buzz phrase "The Internet of Things" thrown around.

The term is meant to describe how all of the technology in our lives, not just the computers on our desks and in our pockets, will eventually be connected together through embedded computing. Not surprisingly, mobile computing has risen to be one of the key players surrounding this movement. The sheer scale of this industry has created both hardware and software conditions enabling unprecedented access to powerful hardware in low quantity for a price that barely warrants consideration.

Don’t believe me? For less than $50, go pick up a Beaglebone Black or Raspberry Pi today (Go! Right now! I’ll wait...) and see how easy it is, within minutes, to be up and running with your choice of OS: from Ubuntu to Android, or even Windows Embedded. Don’t even think about it, just buy one.

From Linux to Android

It’s been a little over ten years since Linux started showing up as a viable operating system choice for embedded. By 2002, surveys were already showing that Linux was commonly chosen over commercial and in-house/proprietary options. Among others, the top reasons embedded engineers were quoted as moving to Linux were (and still are):

- Royalty-free and/or no license fees

- Direct access to source code

- Large developer community for support

The Linux kernel has since proven itself as a reliable operating system capable of providing the stable platform that embedded technology demands. Being based on the Linux kernel, Android provides many of the same benefits that caused the industry to move to Linux years ago, with one additional commercial advantage; licensing.

For better or worse, many companies when developing an embedded device look at the GNU Public License (GPL) attached to a traditional Linux system with disdain because of the responsibilities it can place on that company contributing back to the open source community. Google made it a point to replace pieces of their system, whenever possible, with components licensed under BSD or Apache license; licenses with more permissive language regarding allowing commercial software developed on the platform to remain closed source. This also leads to a side-effect that many of the core Android components, even inside of its modified kernel, were designed from the ground up for mobile/embedded use. There are many in the Embedded Linux community that would like to see these components submitted upstream for their own use (and many pieces have...whether or not they’ve been merged into the mainline is a different story).

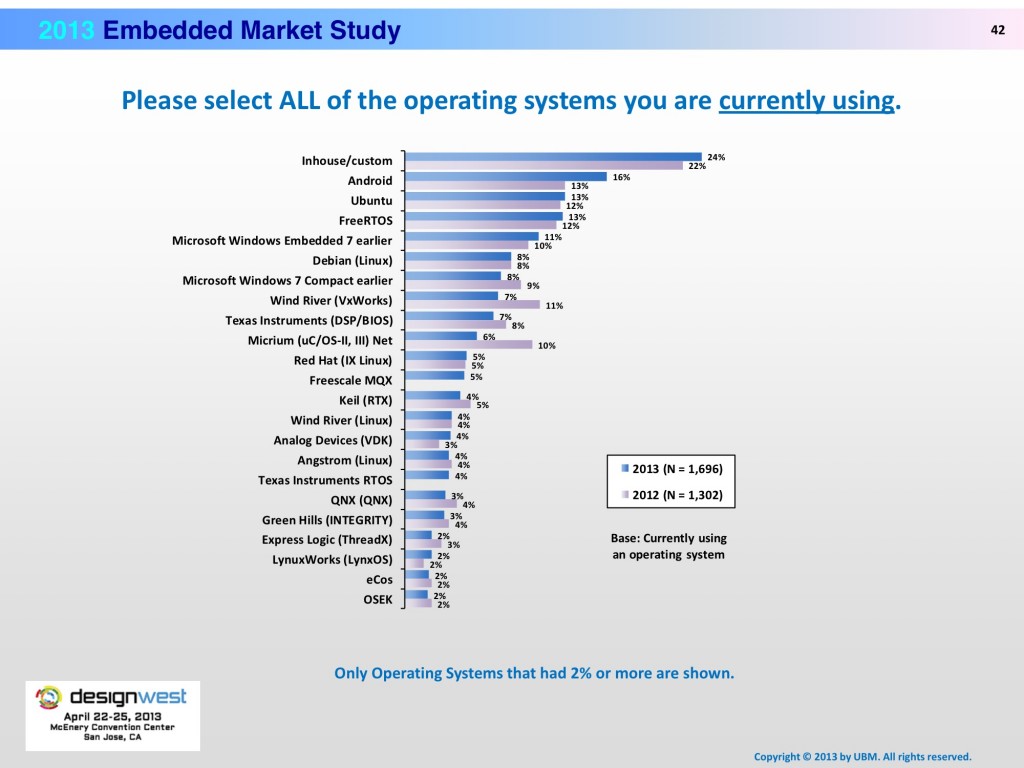

There are many who will argue that the GPL is a key leading to the success of Linux, and that Android’s more commercial approach is not beneficial to open source as a whole. However, it is hard to argue with the fact that many companies looking at the two side-by-side would prefer to have the licensing options afforded by Android. The 2013 edition of the Embedded Market Survey conducted by UBM Tech Electronics every year also provides some telling statistics on how the embedded community views the Android platform. 16% of engineers surveyed indicated that they are currently using Android as their embedded operating system of choice; which is second only to using a custom, proprietary operating system. When asked what system engineers would like to use in the next 12 months, 28% indicated they plan to use Android, which was the number one answer.

Reducing Time to Market

In a recent Businessweek article, Android was noted as being a big part of this movement; and the reasoning behind why is summed up pretty well in the following snippet:

SAIC Motor...developed an Android infotainment system for its cars. "I ran into them at this trade show where they were placed next to all these other carmakers with massive software teams,"... "They said, 'We just have six dudes and Android.' "

This captures the essence of Android’s greatest strength as an embedded platform: its application framework. A handful of developers can create a lot of great software in a very short time, relative to traditional embedded platforms. With the momentum created by the consumer mobile applications space, the size of the Android developer community is huge. There is little difficulty in finding developers who are familiar with the platform and can quickly jump in to create applications. This is especially useful if your goals include opening up your device to development with trusted partners outside your company.

Android provides a nicely packaged distribution of the Linux kernel with a stable and consistent API for applications. It provides a consistent and efficient way to create applications for today’s set of customer expectations; such as touch interface, multimedia, and richly animated graphical UI. The UI toolkit of Android is its greatest asset to the embedded world, and one that it continues to hone as the consumer market further demands that Android run well on a growing variance of different device types and screen configurations.

Not for Everyone

Now, this doesn’t mean that Android has completely taken over the embedded space by any stretch of the imagination (nor is it meant to); just as Embedded Linux distributions do not cover 100% of the market. Many embedded devices simply do not require the hardware power needed to run a full-fledged operating system, or the design complexity that it adds. Beyond that, even in applications where Android is viable, there are still concerns that keep Android from completely eclipsing Embedded Linux and its peers in the embedded space:

- Stack complexity. This can lead to longer than desired boot times while the stack initializes.

- Footprint. That complex stack takes memory, something your embedded system may not have to spare!

- Inflexible outside the designed use cases. Anyone who has tried to add a communications interface or sensor (and cleanly get it up to the application layer) that was not originally part of the framework knows it’s a challenge.

Engineers with applications that are very memory constrained (which in some cases may preclude you from using an OS at all) or have very specific timing requirements may also be putting more work into making Android useful than really leveraging the framework and tools it provides.

What about Google?

It’s worth noting, as many open source champions have voiced, what happens to Android if Google decides to go a different direction tomorrow? Many large open source projects are managed by a consortium to ensure that no single entity can be responsible for the project’s success. Furthermore, does Google really even care about seeing Android in devices where they can’t stick Google Search and Google Play? While I would call these valid concerns on the surface, I don’t think that at this point in Android’s history it’s anything significant to worry about.

Last month, the Wall Street Journal published an article, that was subsequently picked up and commented on by much of the tech press, about Google making a series of additional pieces of non-traditional hardware powered by Android. If you look closely, this isn’t the first indication that Google has eyes (or at least a heart) for Android in embedded.

In truth, we saw Google start to embrace this side of the market with the release of Android 4.0 to the Android Open Source Project (AOSP). Every release branch of the AOSP tree has along with it a number of built-in device targets that the platform can be built for (typically all the current Nexus devices that are capable of running the given version). When Android 4.0 hit AOSP, one of the devices in that list was the Pandaboard, an open source hardware platform based on the Texas Instruments OMAP processor. In Android 4.1, primarily to align with the release of the Nexus Q, hooks for running Android “headless” (i.e. without a display) started to show up in the sources.

So, with each new Android release the underpinnings of making Android more friendly for embedded devices is apparent. Even if the motivations behind this activity are purely selfish for Google (and, make no mistake, I think in many respects they are), that activity still aligns with the goals of enabling Android in embedded. With the momentum they have generated in the mobile space, it is unlikely that Google will abandon Android anytime soon. However, even if they did, Android and its sources are now pervasive throughout the web. It seems a bit naive to think that another entity or group wouldn’t take up the reigns and continue the project forward.

Android isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. While it is here and being driven forward by the immense juggernaut that is Google, it provides an amazing opportunity to create some of the same great experiences mobile apps are known for and bring that to the rest of the technology that enriches our daily lives.